February 13, 2016 -- On holidays, before the school fills with kids and candy, the hallways hush. Like the calm before a storm, it’s a precursor to the sugar rush that amplifies attention deficits and reminds us that our students are children who spend a lot of time inside and receive very little recess.

On Valentine’s Day, the noise level in the hallway - despite our best efforts - reached jungle status 5 minutes after the kids started arriving. They were still talking about who had talked to whom at the Valentine’s dance; they wondered who had bought whom a goody bag; they started trading sweet gifts and notes they had prepared for their friends. Some of the boys proudly sat with teddy bears on their desks, ready to give them to their crushes. SHHH don’t spoil the surprise dude!

You couldn’t tell them otherwise - they were going to give out candy to their friends and they were going to eat the candy their friends had given them. Starting at 7:15 am, I had kids run in and leave DumDums and heart shaped chocolate boxes and candy roses on my desk (no complaints). During class, they surreptitiously dipped candy sticks into sugared chile powder, left FunDip in their desks, and pulled notes off of Reese’s Cups and candy hearts. They traded chocolate hearts with their friends. They had chocolate around their lips.

This sweet goodness, this excitement, should be celebrated. I saw the shoebox Valentine’s mailbox one of my girls had created and remembered the extreme care and thought I had put into my own Valentine mailbox. In 4th grade, I think I actually followed the instructions from Martha Stewart Living. And yet - there was something toxic about this sugar rush. I stress ate mini Kit Kats all day because it felt like I was putting out fires without pause:

A hit J, who had red sugar around his lips, and E pushed L who hit him back. I and D chased each other around the classroom and R came and sat in the back of my room because he didn’t want to go to math, eventually joining the fray between D and I once I had gotten them to calm down. I said bad things about A’s mom across the room.

I practically pushed them outside for recess, picked up candy wrappers with two students while watching them run and play soccer. I talked with I about his behavior. He appeared to see me for the first time all day. “I’m sorry, miss,” he said. “I just feel like I have all this extra energy to get out.”

After lunch, the swell appeared to have calmed. Then R started sweating and making loud noises. This made O stop working. J wandered around the classroom working his way to the bottom of a box of candy hearts, teasing N for liking Josh (because, as I later told N, who was crying, he really has a crush on her).

“R is hyper,” one of the kids observed, sounding hyper himself. “He was eating chocolate in the bathroom.” R., who is pre-diabetic and may carry more serious psychological diagnoses, was making loud noises and picking up and putting down a desk. On his way out of my classroom, he pushed into a child and broke his glasses.

I had set a goal to be quietly firm, after a week in which my kids had seemed to forget how to follow instructions. I was tired of chit chat, so deeply wanting to push them to work hard and think critically. I told them they’d get one warning, and then detention for any choices to misbehave. When it turned out, holy moly, I was serious (Miss Parker is undergoing a transformation), they protested. Pues no. Arms crossed. I won’t stay. In my last period class, a student who has diagnosed anger management issues stood up three times and started to pick up his chair, shaking furiously. He yelled at another student. The class roared, called him a dinosaur. Ricky got too close and got three hits to his stomach.

At the end of the day, 12 hours after it had begun, I ran out of my candy coated room. I felt stubborn, hyper with reaction; I had said no all day, called parents, given detention, moved desks to face the wall. I hadn’t backed down; it had sort of worked. But I felt a sad disbelief at the poor health and disobedience. I wondered if I had been too mean. How could I not have told them how much I love them on Valentine’s day? I thought I was showing them by holding them accountable to high expectations, but maybe my firm energy was toxic too.

We had a teacher’s work day the next day. Thursday’s chaos, harshness, had vanished. The school was quiet and my room looked a lot cleaner than I had remembered it. We did a training on English Language Learners in the computer lab. Something was missing. I walked to our 4th grade hallway, where 35 kids were sitting in a special writing training with a fantastic consultant who projected joy and energy. The room was calm and quiet. The kids sat in their street clothes, no uniform. Some of the boys had gotten fresh hair cuts, some of the girls wore dresses. The group by the door smiled when they saw me and a few kids whispered Hi Miss Parker! Shh, I said, work hard, and left, melting a little. I was so happy to speak to them with love.

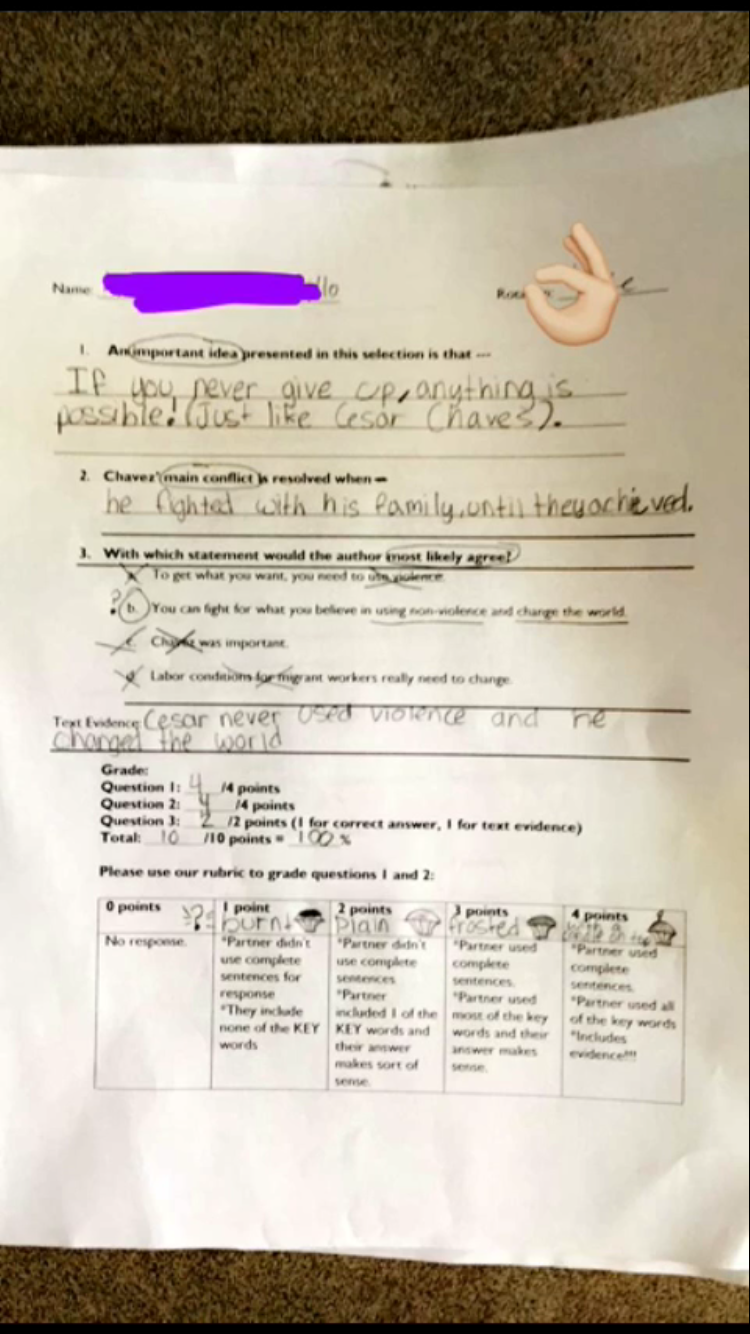

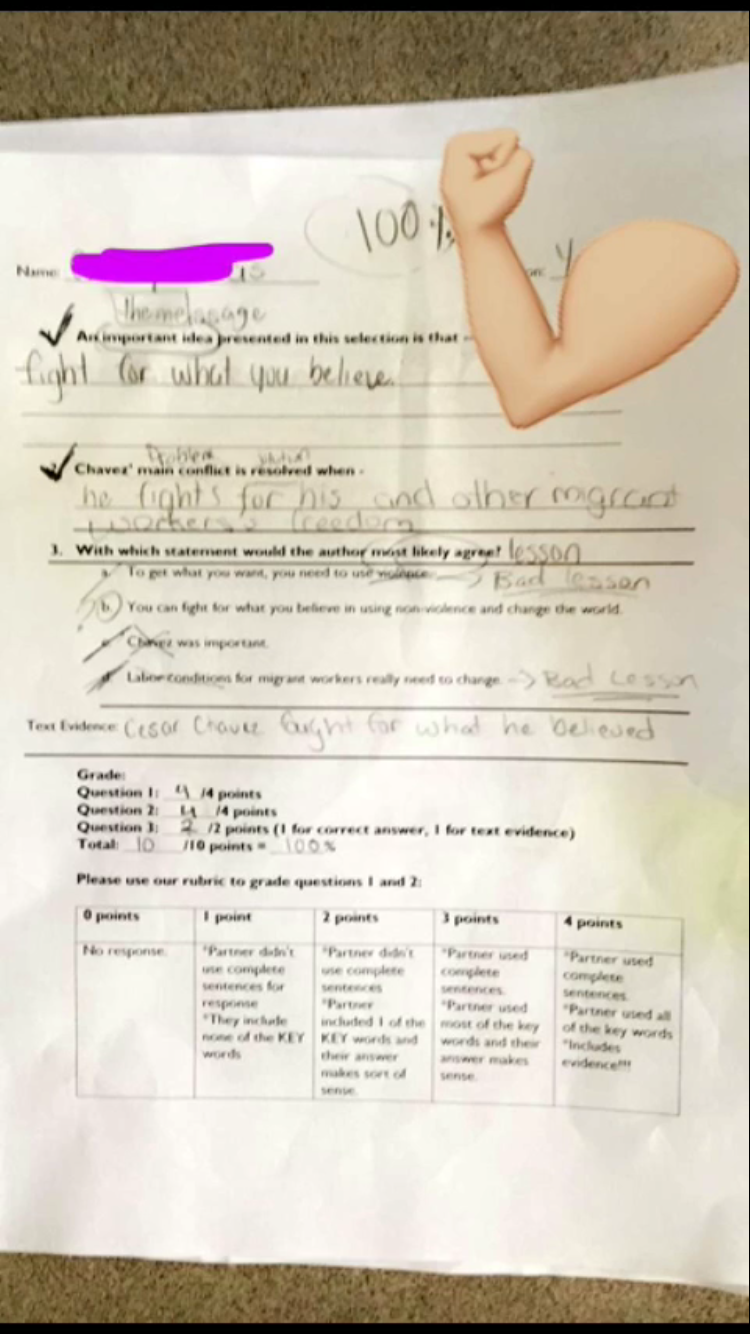

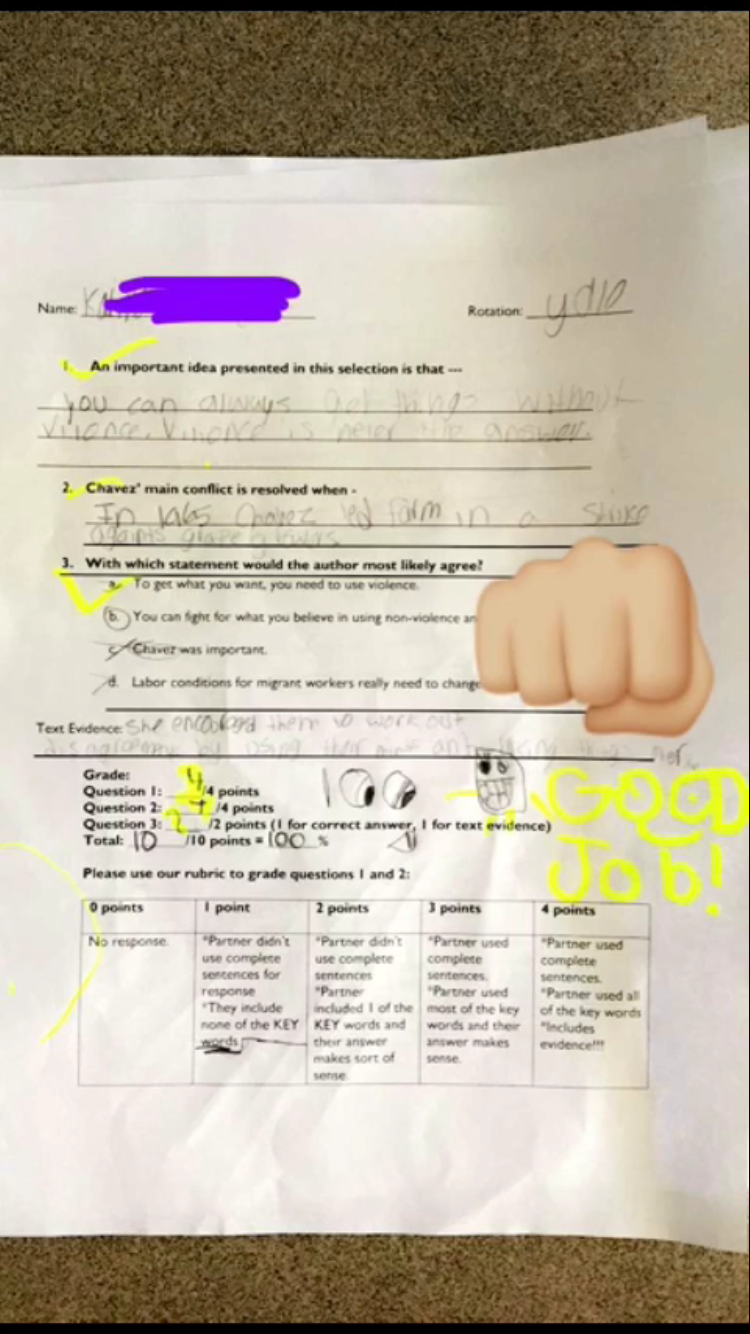

I snuck out of our training again when I heard them in the hallways going to lunch. They ate pizza and hugged me, sang a new song about pronouns. I felt so proud of them, then, and so in love. I remembered all the things they had done well that day before - kids sitting tall, listening, answering questions on sticky notes about their books. 100s on vocabulary quizs, two bold kids who performed the bonus question raps they had written about their best friends. Kids who used to tell me they were bad at reading who had told me, Miss, I’m getting better.

At home, I opened one girl’s Valentine’s Day note to me. She had packed it in a sheet protector inside a teacup that says Siempre juntos, always together. She had asked me twice, have you opened it? Do you like it?

I have loved very few things more.

Dear Miss Parker, the note says. Thank you for always supporting me. I know someday our hard work will pay off!